The increasing loss of public access to beaches, coastlines, parks, and other green spaces across Caribbean cities has been particularly concerning. As the power of tourism and other development interests grows, these ecologies are rapidly being expropriated and commodified for private profit. In this collaborative issue, C-Tek (Naomi Coke and Tedecia Bromfield) shares the personal stories of the founding families living along Bob Marley Beach - a popular beach on the outskirts of Kingston and St. Andrew.

REFUGE IN PARADISE

When entering Bob Marley Beach, one feels like they’ve almost entered a paradise. Veering off the roadside, not too far from Kingston, you enter a beautiful dark-colored sand beach interspersed with ponds of fish, wild guinep, and cerasee curling through the sandy soil. Rastas sit around a fire. Their children and grandchildren play in the ocean, laughing. You sit in the coconut thatch and cane grass cabanas to look out on the horizon. And best of all: you are able to experience all of this beauty for free.

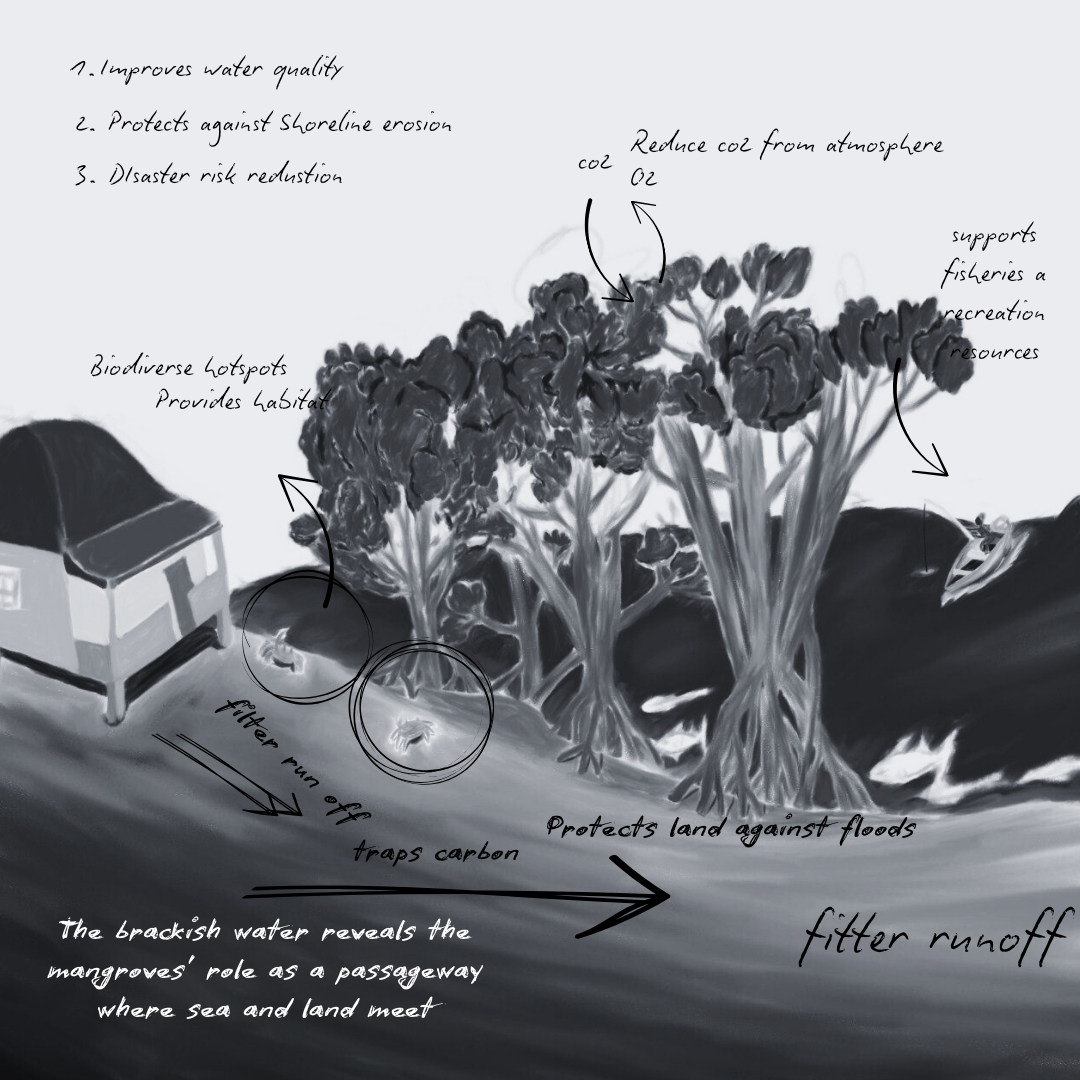

But as you bask in the beauty, you may not realize that interspersed with the volcanic sand, mangroves are growing- their rhizomes forming thickets, transforming sand into forests, critically supporting the nature you have access to. These salt-tolerant trees create a bridge between the sea and the land. They quietly nourish the community, holding together the soil, supporting biodiversity, fuelling the local fishing economy, and protecting against storm surges. Like the mangroves growing beyond the shore, the community’s resistance is rhizomatic; rooted in many directions, extending laterally through generations, neighbors, rituals, and ecosystems. It is not top-down; it is collective, adaptive, and alive.

The Rastas sitting around the sacred fire, specifically the Stevenson and Thomas families, are responsible for the current accessibility and abundance of Bob Marley Beach. In fact, they are descendants of Nyabinghi House members, and the site is home to Jamaica’s first Binghi priest center. The Thomas, Stevenson, and other Rastafari families (including Bob Marley's) have been stewarding the beach since the 1960s after fleeing government persecution in Back O Wall and Trenchtown.

Resting in the cabanas and looking out to the sea, you shift your gaze to the right. A slightly distant marl (a limestone-based material used to make concrete) quarry comes into focus. Similar to bauxite mining, marl mining[1] is polluting the water and air, displacing communities, destroying ecologies, and exacerbating natural disasters (Ayiti Kanpe Min) like the recent hurricane Melissa.

After all these observations, you realize: this paradise you are experiencing is being threatened on all sides:

THE LEGACY OF RESILIENCE:

To learn more about the legacy of Bob Marley Beach, Tedecia Bromfield from C-TEK and Field Notes from the Archive sat down with Camala and Vackiah (aka DJ Fya Locks) Thomas to discuss their family’s history and the reality of displacement, environmental stewardship, and communal resilience.

Tedecia: Can you tell me a bit about how you came to live here?

Camala: I'm Camala Thomas, and we're the third generation living here in Bob Marley Beach. My grandmother, my father, and my mother came here first in the 1960s. They came here after Back O Wall [and Trenchtown] [2], and this is where they found refuge from the government. The Nyabinghi House also found refuge here. They’re still here, but on the other side of the hills.

Back then, there was no entrance to this place; it was all wildlife and bush. Not even a bicycle could come in here. The place we’re standing on now? Completely inaccessible back then. But you know, they were resilient. They survived. What you see now is the product of those times from back in the ‘60s.

ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE & LAND STEWARDSHIP:

Tedecia: What does living here on Bob Marley Beach mean to you, and how do you maintain the land?

Camala: Honestly? Everything. Peace. Tranquility. Good vibes. Fresh air is more precious than diamonds and gold. You feel me? We’ve built everything here from scratch. When my grandparents and parents came, there wasn’t even what you’d call a "chapalin", there was nothing. The trees grew like canopies. They lived under those and started improvising until they could build something proper. It was truly from nothing into something. Now, we farm. That's one of the main things. But water isn’t always sufficient, so we catch what we can: peppers, tomatoes, bananas, mangoes, little apples. The more water we get, the more fruits we can grow.

We preserve the space by not allowing people to come and move sand or dig things up. If someone wants to carry a few stones in their hand, sure. But not truckloads or baskets full.

Camala: This is a volcanic sand beach. People keep saying it’s black sand, but it's not. It's green sand. I found out one day while walking with a German guy he said, “Wow, green sand beach!” That made me look into it. Growing up, we’d catch the sand with water in our hands and see the beauty. When wet, you can really see the green color. It’s volcanic, this side of the island is volcanic, and that’s what gives it that look. When the sun hits, it gets real hot too. The sea used to be way out. You had to run and stop and run again just to get close.

There are [also] two [ponds]. Fish live there. After heavy rain, when the ponds overflow, you see crocodiles coming out just enjoying themselves. There's another pond down the road too. These mangroves they’re critical. They help keep everything balanced. They support the fish, the wildlife. When we had all that rain recently, the ponds flooded and the crocs were everywhere, just having a nice time. Take care of nature, and nature takes care of you. Destruction of the mangroves is the destruction of life. They feed the fish. We can get food from that system. There’s a lot of perch and other fish in those ponds.

Camala: My father, may he rest in peace, fought for this land, and now we’re continuing that in his honor. In the future, we want to build a museum where people can come and see the glory of what it was, compared to what it is now. We have so much to share. That’s why we’re preserving this. We can’t let someone from nowhere come in and destroy all these roots, this culture, this history. That’s why we stand strong as a family. We need beaches and rivers. They keep us relaxed, de-stressed. In a place like Jamaica, who doesn’t need water? The sea is therapeutic. It does so much for us as living beings.

Tedecia: You mentioned people trying to come in, what's happening exactly?

Camala: Private investors. We don’t always know who, but sometimes we do. Some work undercover until bigger ones come in. Even the government has sabotaged us. Let me tell you, this is important. People here pay bills, taxes. This place is a major attraction in St. Thomas. Yet, the road isn’t finished[3]. It’s maybe 80 or 90% done, but they haven’t even put up a sign showing that there’s a left turn to Bob Marley Beach, not even for the community. That’s sabotage. They also built a hill where a gully used to run. If a heavy rain comes, the water would rush down and wash out the whole beach road. It’s dangerous.

So yeah, it’s sabotage. I don’t like saying it, but it’s true. On top of that, international and local private interests are fighting for this place. We’re not against development, but we believe in inclusiveness. If someone wants to develop here, they should come and talk to us, and respect nature. We have two ponds at the back with wildlife. If you’re building here, respect that nature was here first.

But the investors? They don’t even meet us. They don’t say, “Let’s work together.” We don’t see any faces. It’s like ghosts. You asked how we knew they were trying to push us out? One day I was doing construction on part of my kitchen. Then JaBBEM, a group that fights for beach and river rights, reached out. People started calling my phone about news crews coming here. Next thing I know, my workman tells me they came and demolished the place with no notice, no approach, nothing. It fell on the Thomas family to fight a court case, and we’re still in it.

And it’s not like we don’t have our paperwork. We have our land title. We pay our dues. We’ve crossed all the T’s and dotted the I’s. But they’re saying they own a piece of the road, the concrete in front of us. So we’re in court to make sure that road stays free. We’ve seen what happened in western Jamaica when people buy land, block off roads, hire security. People show up with guns. You can’t even pass. We’re not waiting for that here.

Tedecia: What is being done to stop these private investors?

Camala: Thankfully, JaBBEM is helping with legal fees. And we’ve also received support from the Marley family. Give thanks to Stephanie Marley. When they sabotaged us, they cut off our electricity. They paid off the man who owned the light posts, and he sold us out. So we had no light. But, Stephanie [Marley] gave solar systems to both the Stevenson and Thomas families so we could survive. We hold monthly fundraisers every last Saturday of the month.

Camala: This is the site of Jamaica’s first center for Bingi priests. Bob Marley lived ten minutes away, and used to come to the beach to learn. Bunny Wailer has a house on the hill. Most places associated with them are turned into museums. But this is a public beach space, so we’re preserving it differently. We teach the youth. The fourth generation is learning. They’ll eventually run the businesses and control things. We believe in generational responsibility. We might not always be here, but we have to leave something.

The Bob Marley Beach community, much like the mangrove ecosystems they protect, demonstrates a model of interwoven ecological and social resilience. Their resistance is not just reactive it is regenerative, rooted in cultural continuity and a commitment to living symbiotically with nature.

As development pressures mount across the Caribbean, this case urges us to rethink “progress” and look toward community-rooted ecological justice as a sustainable path forward. Sustainable paths do not only affect local communities but all of us Jamaicans, and by extension, the rest of the world. Governmental and foreign agencies that aim to privatize the land and enact initiatives such as mining, resorts, etc, cause pollution, life-threatening health issues, and environmental disasters.

Let Bob Marley Beach stand not just as a symbol of Rastafari heritage, but as a living template for land-based resistance. Environmental justice as a movement demands that communities have the right to live and thrive in safe, healthy environments with meaningful involvement in decisions around the land and environment. The land; the sand, soil, mangroves and shells that make up this beach are a birthright - we deserve to have access to steward our ancestral lands. The legacy of ecological protection is found within the practices of those who have been honoring the environment for generations. 'If alligator com fram di riva batam a tel u se shaak dung de, bileev im.'

To learn more about the Bob Marley Beach family’s efforts please see the resources below: