HOW IS EXTREME HEAT IMPACTING WORKERS?

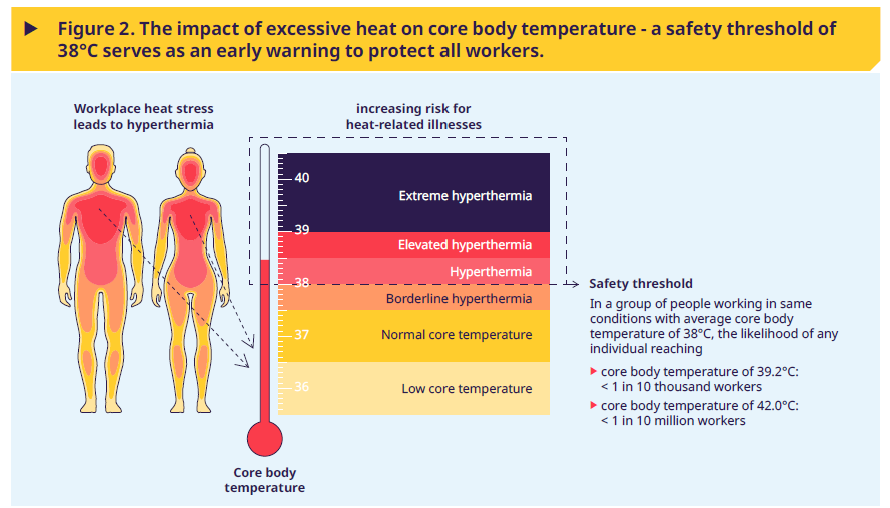

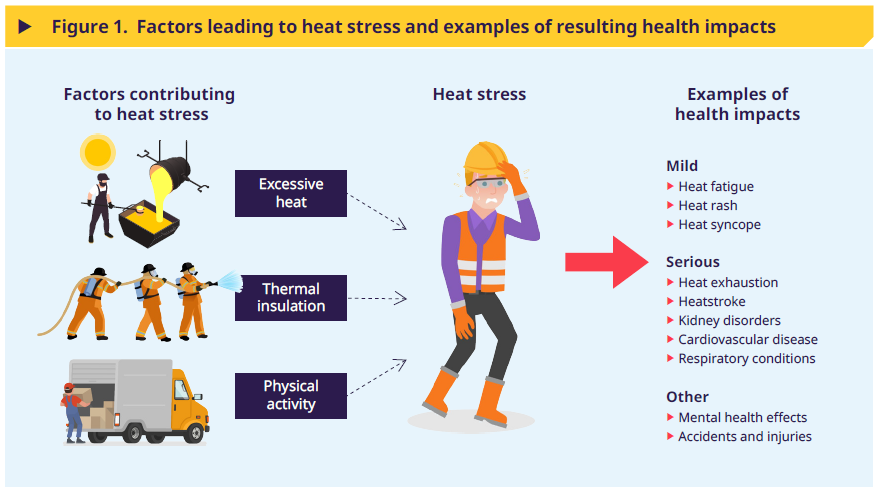

Temperatures across the Caribbean are warming, and they are affecting everyone, especially workers. The International Labour Organization (ILO) notes that both indoor and outdoor workers can face these risks when they are exposed to heat for longer periods and greater intensities. In terms of basic biology, a core body temperature of 37oC is essential for normal function (Flouris, Graczyk, Nafradi, & Scott, 2024). When excess heat is stored in a worker’s body, it will raise core temperatures, leading to elevated skin temperatures as well as increases in skin blood flow, heart rate, and sweat production. If body temperature rises above 38°C, physical and cognitive functions are impaired; if it rises above 40.6°C, the risk of organ damage, loss of consciousness, and, ultimately, death increases sharply (Smith et al.2014).

Island City Lab was interested in understanding who the workers most at risk of heat stress in the region were and how their built environment was contributing to or being used to prevent these dangerous conditions. We spoke with Jason Glaser of La Isla Network, based in Central America, and local Firefighters, all members of the Jamaica Association of Local Government Officers, about how workers are dealing with the heat.

SUGARCANE WORKERS IN NICARAGUA:

La Isla Network is an occupational safety and health research organization that works with organized labour, large employers, and multilateral funders to improve working conditions. By leveraging international trade deals, they are able to push employers to invest in life-saving heat mitigation infrastructure and safety procedures to reduce worker exposure to extreme heat.

“We envision a world where workers are protected from extreme heat and all other environmental exposures, ensuring businesses are productive and governments and multilateral institutions benefit from a protected workforce” (La Isla Network, 2025). While working in Nicaragua, CEO Jason Glaser learned of a community of sugarcane workers devastated by chronic kidney disease. As the organization's self-produced video explains;

Throughout our conversation, I could not stop thinking about the generations of Caribbean labourers working on sugar plantations whose lives were cut short in part due to heat exposure and this mysterious disease. I asked Jason if La Isla had ever worked in the Caribbean, and he mentioned a failed proposal that would have brought their research and advocacy to Jamaica. Through his short stint in Jamaica, he was able to identify key differences in sugar cane labour practices in Jamaica versus Central America. He observed canecutters in Jamaica leaving the fields when the time was too hot, only to resume work in cooler temperatures – this signified in his words “a less hierarchical” work environment than existed in Nicaragua, where workers, due to management pressures, had to stay working even during the worst part of the day’s heat.

FIREFIGHTERS IN JAMAICA:

In June, we reached out to the Jamaica Confederation of Trade Unions (JCTU) an umbrella organization representing multiple trade unions, to see if any of their members were raising concerns about extreme heat exposure. This inquiry directed us to the Jamaica Association of Local Government Officials (JALGO), which represents several public sector organizations, including the Jamaica Fire Brigade, Emergency Services and National Water Commission, and National Irrigation Commission.

DD: Generally, we understand what firefighters and EMTs do, but it would be helpful for you to walk us through what an average week looks like for you.

SB: Alright. So, being a firefighter means being the first one on the scene in most emergencies in Jamaica. The only emergencies firefighters aren't the first responders to is crime and violence. But basically, most emergencies, health, accidents, fires, and any other that require professional response and relief.

DB: Right now, we find ourselves responding to a lot of bushfires and landfill fires, both start happening around this time of the year. So basically, we just go and prepare ourselves mentally and wait for the next emergency call.

CW: For me, I supervise the EMS staff. We have one ambulance that we respond with, and we have 12 persons who man that section. There are 3 persons who work per shift and respond to medical and trauma emergencies.

DD: Are you observing increasing temperatures? How is it impacting your work?

SB: We are seeing temperatures of36O, 37O, 38OC sometimes, and that's not what you would consider on a normal day. And then we firefighters are deployed in a bushfire or a house fire setting where the temperatures are elevated much higher. We are not only seeing more bushfires but also more drought situations. Yes, we always have a dry season but we recognize that droughts are longer because there are times when we go to certain communities to replenish our water and have to leave because there's no water in those communities.

CW: As it relates to heat peaks due to climate change, we tend to get more calls because people have lower capabilities of adapting. They may have [health] conditions that become more severe based on the heat. Since last year, we can see increases in emergency calls for the elderly and persons with sickle cell—once there's extreme heat, we are getting called.

It's almost like we are in one constant summer. For the past 3 years, it seems like summer is getting longer and longer rather than just being July, and August. Even though we have what we call bushfire season, which marks a dry period on the island—usually March and April—due to climate change, sometimes the season starts earlier, like January. Conditions become drier and warmer than usual. In a sense, it's almost like the whole year is summer.

DD: Can you talk about the physical labour involved with your job?

SB: While we have various strategies we employ, our job is largely physical. We utilize water from fire trucks to extinguish fires, and that entails moving hoses from trucks to the point of the fire and that requires manpower. When dealing with rescues from say, a crashed car, it will require us to utilize a variety of tools that require the exertion of physical strength.

DB: Some may say it is easier to go to a structural fire than a bushfire, because a structural fire is normally confined to a specific area. Now, a bushfire can sometimes range between 2 acres to up to 10 acres of land just burning. Now, when you go to the landfill fire, it's a whole different kettle of fish, because you have fire burning, debris burning and it is not something that they can just put water on. Sometimes the fire is actually beneath the surface. So you have to basically saturate the entire area with water. You have to spend hours on a landfill fire. With bushfires, we say that the terrain has a lot to do with it. Many times no one caused the fire but because these hilly areas are pure limestone, we find that the rocks are igniting based on the heat - they are self-igniting.

CW: For EMS, once we arrive on the scene, whether it's at their home, on the road, or at another location, we have to secure the scene. Then we have to lift the patient onto the stretcher, into the ambulance, and from the ambulance into the hospital. We may not be fighting fires, but we still have to perform physical tasks for patients, as well as navigate challenging locations like hills or uneven terrain. So it's still physically demanding.

DD: What are the conditions like within the facilities/buildings you work from?

DB: I am stationed in Ochi, and we have no air conditioning at the brigade. Once it hits 1, 2, or 3in the afternoon, it's basically cooler to sit outside under a tree than to stay inside. At another brigade, female staff did their own fundraising and found sponsors to purchase 3 AC units for their station. The only support the brigade provided was labour to install the units.

But beyond ACs, we need an improvement in the mentality of leadership. When someone starts off as a clerk and moves up in the ranks to a supervisor, that person automatically forgets the struggles of being a clerk; they forget all the hard-life involved with being a clerk. It's like they don’t remember being a firefighter and sleeping in a dorm, 18of you with no AC and limited ventilation (because these buildings were built before you and me were born) - so it is extremely hot. And [leadership] doesn’t remember this because they no longer sleep in dormitories. And that happens in every form of work - as soon as we leave the post, we forget the struggles of it.

DD: There is a long-awaited Occupational Health and Safety Act that has been in draft for a few decades. What are your thoughts on the importance of that legislation?

CW: It's very important for any organization because you have to have standards for safety—conditions you work under, how you work, exposures, and dangers of the job itself. The actual documentation was developed in the 1990s and revisited a few times, but I'm not sure where it stands now. It's something that is cash-reliant, and based on the physical changes needed across buildings in the country, it's been slow to be enacted.

DB: I don't see that being passed anytime soon because of the [employer] responsibility that it comes with. With the act, if our AC breaks down, the brigade would have to come and fix it- the types of conditions people are now working in would be a thing of the past. It is going to cost a lot of these employers too much resources and responsibility. I think our unions have not done enough. You have to remember that every trade union is a fourth generation of a political movement so when they embark on some mission, they will go so far and no more, because of their political origin. I believe, honestly, it[political allegiance of unions] is an obstacle, because if the union is not aligned to a party they will be more aggressive, and have zero tolerance. And then with a different party, they are more understanding or relaxed.

SB: We need the Act because it will make employers more responsible for dealing with their workers, protecting their workers and creating better working environments. In terms of the heat factor, I am not certain if the Act deals with that. From my knowledge, it largely deals with buildings – but this is something that I would have to review before speaking on it. But this might be something that the unions will have to try to get inserted in the law, because, you know, laws are made to be amended.

DD: Yes, of course, because if it was drafted up in the eighties, obviously, climate change wasn't as big a concern then as it is now, right? So it feels like it's almost essential that a review happen to include some of these issues that you guys are experiencing. If the Act should pass tomorrow, what are the big improvements that you would see as a firefighter?

DB: All right, if the act passes tomorrow, I would see people taking more interest in their work and people being less frustrated. People will value the work more because some people are just here [The Fire Brigade] because this is the best option they have. But if at any time, an option that is even 1% better should present itself, then they will leave. They would leave because some of them are fighting fires without the necessities; they may not have any gloves, they go to fight a landfill fire and inhale all manner of chemicals, and they do it without any breathing apparatus. Nowadays, we are responding to hybrid vehicle fires or collisions, and we don't have the proper gear or equipment to deal with them. (These hybrid vehicles push current up to the thousands and are heavily electrified.)

DD: What are the other work essentials that are critical for your work – water, hydration, etc.?

DB: Sometime, if we don't get it [brigade provided water on the go], we have just make up and buy one case of water and put on the truck. Sometimes, when you go out on the scene,the officer in charge, depending on the type of person he is may say, “Alright, let me buy one case” and he might buy that from his own pocket. He might never get it [the cash] back. So if you go out with somebody, that doesn’t have the money, ‘dog nyam your supper’.

DD: From the union’s perspective, what are the efforts that are being taken to prepare the workforce for increasing climate impacts such as extreme heat?

SB: My union JALGO has been advocating and engaging directly with employers like the Fire Brigade to get improvements implemented that address climate change challenges. We have been advocating for improved PPE [Sun protective gear, including hats, shades, etc] as well as improved infrastructure at the station [like air conditioning]. We've also advocated for a change to work scheduling to reduce sun exposure for workers. If we allow workers to work longer shifts, they will also have more time off from work. We believe that this will contribute to less heat exposure.

We have also partnered with the Global Federation of Public Services International to see how best we can understand climate change on a local and regional basis, and use that to improve how we dialogue and lobby with employers like the Brigade.

Also, the ILO [International Labor Organization] recognizes that a just transition is something that has to be at the forefront of our work and advocacy and they have chosen Jamaica as one of the first pilot areas to really look at for policy to guide labour and climate policy. So they are meeting with stakeholders over the next 2 years to analyze all the policies we have and how they can be improved to make a more inclusive environment.

So yes, we welcome that, but what does it mean? Does it mean that the guy who works at JPS will no longer have a job because we are trying to reduce GHG emissions? Or will it mean that JPS will have to provide retooling and upskilling opportunities for workers so that they can transition to repairing or maintaining solar panels of electric vehicles and all of that. And how do we make the transition from our current context to a workplace of a greener economy? So yes, we are all for the “green economy,” but will it make sense for the workers and will it make sense for people in society overall?